The West Wing – And It’s Surely To Their Credit

Because of you I am a good nurse.

My favourite preceptor never introduced me as his student nurse to the surgeons, I was always his sidekick. The first time I played scrub nurse it was for the morning orthopaedic list with the upper limb surgeon. After I carefully scrubbed in his presence, managed to slip on both sets of sterile gloves without ripping them, and didn’t contaminate myself all the way to the operating table, I went to introduce myself to the surgeon. I was terrified that he’d refuse to have a student nurse on her first day in theatre scrub for him. He had every right to feel that way too – I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. My preceptor slid in beside me, freshly gowned himself, before I could even speak .

“This is Dannielle, my sidekick, she’s gonna scrub for you,” he said, and even behind the mask I could tell he was grinning.

“Well, goody,” the surgeon said in his polite British accent. “Skin knife and artery forceps to start please sister.”

“Yes, right away,” I’d said, smiling widely even though he couldn’t see that part of my face.

I spun around and turned to my preceptor in a panic. Which one was the skin knife? I had learnt 10 and 15 blade. What in God’s name were artery forceps? He laughed at my expression and called to the surgeon.

“Ya know Matt normal people say 10 blade and a haemostat, give the poor girl a chance, she doesn’t speak British.”

The surgeon laughed and rolled his eyes, and I handed him the instruments, feeling stupid. My preceptor didn’t allow me to feel stupid for long. He let me scrub for countless procedures, taught me how to be a circulating nurse, and annoyed other scrub nurses until they let me observe their surgeries – a kidney transplant, a liver transplant, an aortic valve repair, and a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). Having a preceptor who teaches with the same passion with which you want to learn undoubtedly shapes one’s career as a nurse, they help make you into the kind of nurse you want to be.

During training, other nurses overwhelmingly influence what sort of nurse you will become when you graduate. More often than not they guide and teach you, showing you how to be a competent nurse, but one can learn just as much from poor experiences, learning about the kind of nurse you don’t want to be, the behaviour you want to improve and learn from. I carry all of these experiences with me as a graduate nurse, because now I am the nurses that taught me, patients are my responsibility, and I have students of my own to teach from time to time. However nurses are not the only ones who influence us in our path to become RNs, there are many reasons we even come to nursing, and so many people who shape those ideas. For my first year as a qualified registered nurse, I would like to pay respect to those individuals and thank them for the nurse that I have become.

The Teacher

I am fifteen years old, in year eleven, hell bent on going to medical school. I sometimes wish I had a curtain to hide myself behind, because the voice in my mind makes it hard to see anything good about me, only problems to be fixed. Control is the only drug I need, and it’s an addictive one, one that leads me to the bathroom lunch time early in September. I have chemistry in fourth period, but my mind is thinking of other things. The ritual is terribly familiar by now. I choose the farthest cubicle, checking to see that there is no one around, and attend to the cutthroat business that is making myself sick. Then I go about the other business – hiding it. I rinse my mouth with mouthwash to kill the smell and get the acid off my teeth. I place a cotton pad soaked in icy water around my eyes to stop the redness and stinging, so I do not draw suspicion by looking like I’ve been crying. I smooth my clothes and follow the command from my mind to act normal. I make it to chemistry class, my facade holding, I make it all the way through class too, even though I feel a panic attack coming on, because a familiar feeling is beginning in my lower abdomen. Pain. When the bell for end of class rings I walk along one of the upper levels of classrooms, away from the rush of people who might notice that my mask is cracking, because my heart is racing, my stomach churning – from anxiety or as a side effect from vomiting it is unclear, but it hardly matters. I see my biology teacher, my heart races faster – I am bad at maintaining this face around him, he sees right through it so often, he is too nice and I feel guilty for lying. But this is a secret that burns everyone who touches it, so I always try. Today something is different though, I don’t know what, perhaps I have managed to wrestle back control from “her”, if only for a moment, because when I smile and wave at him, strolling past quickly, he turns back. When he asks me if I am okay, I say no – against better judgement, against her screaming voice, even though I know it may mean the end of my secret.

I learnt the first thing about being a good nurse before the thought of becoming one even occurred to me. From my high school biology teacher I learnt what it meant to do more than the confines of your job description, because when you care for other people duty calls you someplace higher. To have the privilege to care for, teach, or mentor others as part of your job is to understand that people are more than the task in front of you, they are more than a policy, and more than what you can ever be taught in university. When I told my teacher that I didn’t just spend my lunch times not eating, I spent them throwing up too, I expected him to panic. I figured it wasn’t part of teaching curriculum to know how to deal with teenage bulimics, you just passed them on to people whose job it was to fix them. I expected that maybe he would say that he was sorry, but he had to drag me kicking and screaming to our school’s guidance counsellor – who I was not a fan of. I even expected that maybe he would be sad, and ask me why, why did I do this? How could I like throwing up, perhaps he would ask – like the school’s deputy principal would ask two months later when he found out. He didn’t do any of those things, there was no panic, there was no passing me on, no dragging, For many weeks and months after that day he listened to me, helped me figure out what I wanted to do, and let me realise on my own that I wanted to stop, and was there for me when the time eventually came to tell my parents, he even called my mother when I was too nervous to go home and face her. During this time he never let me forget that I was enough – smart enough, good enough, capable enough, and soon I started to believe it too. He wasn’t obligated to do any of this in his role as my teacher, but he did anyway, because it was what I needed. He realised that what I told him was the hardest thing I have ever told anyone, and respected the kind of honour associated with that. I trusted him enough to tell him my darkest secret, and he never let me down.

My teacher taught me what it meant to be empathetic, and not just do a job, but be genuinely passionate about what you do – enough to go the extra mile without missing a beat. When I admit a patient for surgery, or care for someone on a ward, or attend to an emergency patient, I have a list of requirements that I must fulfil. I must abide by policy, professional frameworks, refer to my knowledge and assessment skills. If by the end of a shift my patient has had their prescribed interventions, I have helped them with activities of daily living, prevented harm, and reported deterioration to doctors – my job is done, legally and professionally. I am busy in a shift, and sometimes there is not time to hold hands or give reassurance – but I do it anyway. My patients are more than a list of tasks to complete, and my job is not just to carry out such a list. I make time to listen to these conversations, because it’s an honour to be chosen to hear them. If a patient trusts me enough to tell me they are scared, I must give them the respect of my attention and my comfort. This comfort isn’t an extra, it is part of being a nurse, and why I became one.

Thank you for teaching me the power of empathy to help and empower another person, because of you I am a good nurse.

The Doctors

Frank

To become a nurse, or any health professional, is to learn a new language – a plethora of jargon and acronyms that become part of your everyday vocabulary. You don’t go to the toilet – pt PUIT. No more do you eat three meals a day, one “tolerates diet and fluid”. To enter an environment where people freely use this language is akin to travelling to a foreign country. This is how a patient feels when they enter a hospital. As well as this new language, one learns a new set of social rules and skills. In real life, we learn our social skills through experience and develop schemas, we observe and put into practice that which we have observed. In nursing world, we have to learn this all over again with interesting new observations. No one ever taught me the appropriate conversation to have with a patient when they’re half naked, or when you’re violating their personal space, or how to ease the awkward silence that exists as you stare at someone’s chest to count their respiration rate. However there is a doctor that stands out who taught me that all of these things can be done, and done well, and his name is Frank.

Frank and I met in my first semester of nursing school and three months after my laparoscopy. I was sent for a scan as a follow up after surgery and to ensure my IUD hadn’t attempted any sort of breakout from my uterus, because perforation of any organ is absolutely no one’s friend. Those endo sisters among you will know said scan as the delightful process where one lies with an ultrasound between one’s legs for twenty or so minutes and tries to focus on something other than the fact that this is the least fun you can have without your skirt on, ever. Frank was uniquely gifted at conversations you can have without pants on. Within five minutes we had covered our shared university alma mater, how he thought nurses were the greatest thing to happen to the world, and several jokes about the absurdity of a former premier’s head. I laughed, I felt comfortable, and yet I still wanted to throw up, and my endometriosis flared up which made things fifty shades of shit. He managed to seamlessly swing from laughter and manner that could only be described as ‘jolly’, to quietly asking me if I was alright and reassuring me that everything would be okay. I am one of those people who cries stupidly when people are nice to me, so naturally I went right on cue. This doctor did not make me feel stupid for feeling this way, he didn’t tell me not to cry or that there was nothing to worry about – because clearly for me there was. He just patiently waited while I let the anxiety out, offering a helpful hand on a shoulder, or sympathetic nod. Then when I was ready he went right back to his jokes.

Sometimes the only way is through. In nursing I cannot dance around the fact that something will be awkward, or that it will hurt, but if I act like I am asking them if they’ve seen any good movies lately, rather than whatever organ system I am focused on at the moment, things go alright. Patients can read you like a book, make no mistake. If you act like what you’re doing is a big deal, or makes you nervous, they will mirror those feelings. Frank taught me the importance of treating the awkward as routine, while still acknowledging the foreign environment the patient finds themselves in. You must be as prepared to make small talk as you are to hold hands, and treat both as a completely normal part of the process. I am still not as adept at these situations as Frank, but I have a standard to aspire to.

Graham

The first time I left Graham’s office, I cried for a long time; it wasn’t because I was sad, not really, despite much talk of surgery and endometriosis. The only thing I was sad for was the knowledge that before this I had accepted less than being taken at my word. I cried with an unusual mix of relief and something unidentifiable, because I had never felt so understood in all my life. I’ve written plenty in the past about how I have been so fortunate to have a great specialist, but it cannot be understated how greatly this treatment has impacted on how I treat my own patients. It’s not only how his kindness, patience, and consideration made me feel better, it’s how it empowered me to trust myself and become my own advocate – because not every medical professional will understand or even try to understand endometriosis, sometimes you have to be the one to push.

No matter how many times I find myself sitting in the same spot in his office, usually three months too late, to tell him that things have not been so good, he acts like it’s the first time I’ve even bothered to ask. There may be some theatrical sighing and a head shake as he tells me that for a nurse I am a terrible patient, but every word I say is taken seriously. If it matters to me, it matters to him. If there is a story that goes with it, he listens. It’s not so hard to figure out what patients want on a basic level, they want to be heard, to feel like what they say matters, that the person they are telling cares. A few times during an appointment he has answered a call from one of his children or another patient, always apologetically. Some people shake their heads when I tell them this, saying that he could have waited for me to leave, but I see it in a different light. The people who call know he is a doctor, and a busy one, so for someone to call and expect to be answered, it must be important. I know from my own experiences that knowing someone needs you and not knowing why can be twice as distracting as just simply answering and figuring out what you can do later, and reassuring that person that they are heard. To me that shows genuine care, and if he treats his family, and his other patients with this respect, then surely I too am in good hands. In nursing it is so often that our care goes unnoticed because it is out of sight – the phone call to a doctor at 2am to demand they come and review a deteriorating patient, the care I take to have a medication checked before administering it – but I am okay with that, because I do not care to be acknowledged, I do it for the patient.

I find myself each day on the ward using some classic “Grahamisms” – a joke he’s made to make me feel better, emulating a reassuring expression, or simply trying to think what he would say if this were me, or one of his patients. All of them have helped me with my own patients. More holistically, his attitude of listening to the patient narrative and allowing it to be one of the major tools for assessment is something that influences my practice. It is the reason I listen with interest as someone tells me the story about their grandchildren, because sometimes it’s important, and give a clue to something we may have missed – depression, decline in mobility, cognitive problems. Patient stories matter, and part of providing true patient centred care is seeing the patient in their world, rather than the artificial and controlled world we create in hospital. Graham taught me that health professionals can make differences in people’s lives, big ones, and though our names might be forgotten, and our faces may fade away in their minds – patients will never forget the care we provided or the safe and reassuring place we created for them.

Thank you for teaching me the real life meaning of patient-centred care, and how empowering it is as a patient to be heard, and understood. Because of you both I am a good nurse.

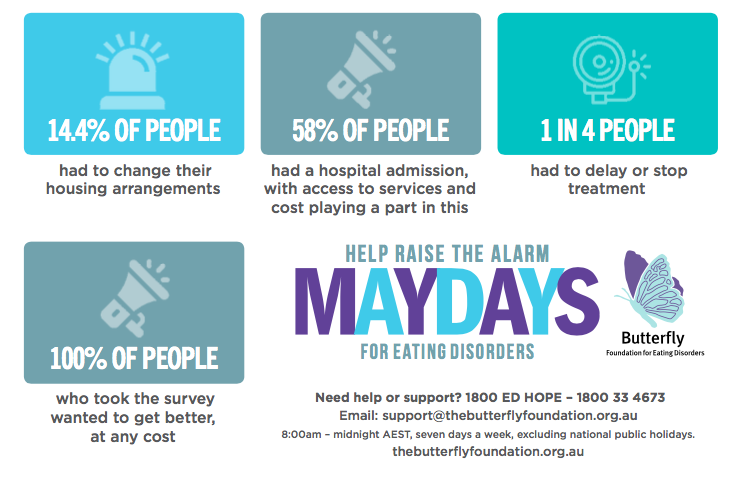

The Matriarch

My Nanna was 77 years old when she died, which seems far too young in an age where life expectancy for women is over 80. The disease was metastatic breast cancer, the cause liver failure, the complication urosepsis. Nanna always wanted to be a nurse, she once told me, a theatre nurse, just like me, so that she could watch surgery all day. Nanna never turned away from blood and gore, she loved it, even when she claimed she didn’t. I was in my first year of nursing school when she received treatment for a relapse of her primary cancer, and was taking my final exams the week she passed away. The day she found out that she wasn’t going to make it, and that mere days remained, she was braver than I thought possible. She held things together after an initial outpour of emotion, she began charging me with the responsibility of making sure each granddaughter would have something of hers, and what of granddad’s would be left to her grandson. She and I attempted on that first afternoon to cram what should have been another twenty or so years of love and life into a short space of time, knowing that each word came from a stolen moment and borrowed time.

On the third day the ward’s nurse unit manager came and told me that she heard Nanna wanted to see her dog one last time, and told us that if we could sneak her in, she would let us. Nanna was already on a NIKI pump, filled with medications to ease pain and keep her sedated enough not to feel any distress, but when Chloe came to sit on her bed, I swear I saw her smile one last time. The nurses sat at the door, trying to catch a glimpse of this sweet moment and smiling. This was a simple gesture, but it no doubt meant everything to Nanna to see Chloe one last time. She saw her three sons, two of her granddaughters, her best friend and her dog – she could go now. She didn’t wake up again after that day and died two days later. The nurses in oncology talked to her as though she were still answering, they did turns and care as though preventing pressure areas at this point really mattered, because my Nanna, no matter how close to the end, was still a person who deserved comfort and care. Those nurses were exactly what I wanted to be, but it was Nanna who taught me what it was like to be the one dying. She taught me that there is no textbook way that things go when you hear that the end is coming, and that it is possible to be brave even when inside you are not. Nanna lived a life for others, and that was how her life ended too – she was strong for us, even when it was us who wanted to be strong for her. At her funeral my father described her with a line from Bruce Springsteen – courage you can’t understand. That has been true for so many patients I have cared for. I look at them and wonder how they don’t just cry all the time, how they manage to make jokes and compliment my hair or my colleague’s tie. They find something, some place inside them, and keep going despite their circumstances. My patients have been the best teachers of all. They help me understand what it is like to be vulnerable or scared, or confused, and that these emotions matter. They are more than their disease. I have been the patient myself, and for so long I didn’t think much of myself, and for that reason I accepted it when people dismissed my pain or didn’t take me seriously. Once I found a doctor who helped me realise that I matter, I knew I never wanted any patient to feel the same way. My patients are the reason for my job, and they teach me something new every day. I see Nanna in them each day, and for her, and them, I do my very best.

Thank you for teaching me what it is to be a patient, how we as humans can handle even death with grace and dignity, and that loss changes families forever; and how I help families deal with that can also change them forever. Because of you, I am a good nurse.

On my final day of theatre placement I scrubbed for the same surgeon as on the first day. Before he even turned to ask me I handed him a yellow sharps tray and held in my other hand a haemostat.

“Skin knife and artery forceps,” I said.

“Thank you sister,” he replied.

“You know I’m not a nurse right? You don’t have to call me sister, I’m a student,” I told him.

“I think I’ll call you sister,” he said. “You’ve earned it.”

My preceptor stood to the side, supervising but letting me do the case alone; I could see his eyes smiling behind his mask.

“Thank you,” I whispered.

To every preceptor, every patient, every doctor, and friend…to every family member, every other student nurse who made it through with me: thank you for making me more than just a good nurse, but a great nurse, a nurse in progress who humbly presents herself each shift to patients and other colleagues to ask – what can I learn today?

To every nurse and midwife reading, Happy International Nurses Day sisters!